The wreck of the Speke

The island’s most sensational ship wreck occurred 112 years ago this month back in 1906, when the Speke, the biggest three masted full rigged ship in the world, crashed on to the rocks at Kitty Miller’s Bay on the islands south coast. Relics...

The island’s most sensational ship wreck occurred 112 years ago this month back in 1906, when the Speke, the biggest three masted full rigged ship in the world, crashed on to the rocks at Kitty Miller’s Bay on the islands south coast.

Relics salvaged from the Speke by residents can still be found on many parts of the island today.

The Speke was an all steel ship, built in 1891, 310 feet long and weighing 2,712 tons.

The ship remained on the rocks for several months before being smashed to pieces on the beach.

Mr W Kennon purchased the wreck for 12 pounds and salvaged a large portion of the superstructure, 80 fathoms of anchor chain, and two anchors, each weighing three tons.

Following this most sensational wreck, the Island became dotted with relics of the catastrophe.

All kinds of souvenirs found their way into houses and sheds, and some

remained in their new homes for 60 or 70 years.

ln 1940,the Speke figurehead was found in Mr Kennon's shed and restored to its original lustre by the children of the Cowes Primary School.

Ventnor farmer Donald Cameron, whose property overlooks the rocks on which the Speke foundered, has researched the events that led up to this disaster.

Extracts from the account he wrote back in 2006, to mark 100 years since the ship went down, are published here.

The wreck of the Speke

According to Champion of Sail – the story of RW Leyland and his Shipping Line The Speke, together with her twin sister ship the Ditton were built by Thomas R Oswald in Milford Haven, England, for R W Leyland and Company in 1891.

The Ditton and the Speke were among the very last windjammers of their type to be built, when steam ships had already been in service around the world for thirty or more years.

Officially, at the time, they were the tallest, biggest three masted, square rigged, all steel hulled merchantmen built in the world.

The Speke carried a greater sail area than any other vessel of her class, and was described in shipping circles at the time as “a noble ship of graceful lines and towering masts.”

From 1905 to 1906, the Speke’s third Captain was William Barton Tilston.

When he arrived in San Francisco he was instructed by his shipping line to assume command of the Speke which lay in Los Angeles harbour.

He only made two crossings of the Pacific Ocean as her Skipper – one trip from Los Angeles to Newcastle, Australia and then back to Peru.

After unloading his cargo of general freight he couldn’t find another load - normally of Peruvian guano (superphosphate) to return to Australia, so came back empty – except for a heavy load of local river stones which provided what he thought was sufficient ballast.

According to the Phillip Island Times, in retelling the story: “One hundred and three days out of Mollendo, Peru, the Speke, on arrival at Sydney Heads on February 10th 1906, received instructions by cable from London to proceed to Geelong to load wheat for the United Kingdom. Under the command of Captain Tilston, she left Sydney on February 12 en route for Geelong. Rounding Cape Howe, rough seas and tempestuous weather were encountered”

According to Joshua Gliddon in Phillip Island Picture and Story 1958:

“On February 21st the ship was lying close into the shore, between Cape Woolamai and Pyramid Rock, so close in that residents of the Island were able to see men moving about on the deck.”

According to some of the evidence given at the subsequent Marine Board Inquiry, May 1906: “During the night of Wednesday February 21, while on a port tack beating down the coast, Captain Tilston instead of continuing his course for Port Phillip, when inside the radius of the Cape Shanck Light, mistook this light for the light on Split Point (Airies Inlet) and kept his ship so far to the eastward that he set a dangerous course.

“On the Thursday morning the ship was close inshore (off Pyramid Rock) and heading parallel to the rocks on the southern side of Phillip Island (at Berry’s Beach and later off Helen’s Head).

“Apparently the ship refused to wear around and bear up, and everybody on board realised the seriousness of the position. As she was in ballast, her great height above the water offered a resistance to the wind and sea which counteracted the effects of sail and rudder. Even if she had worn round on this dangerous course it is doubtful if she would have avoided the perils of the coastline.

“Captain Tilston in trying to avoid disaster let go the anchors but one of the chains parted and the other anchor dragged. One crew member was reported as saying: ‘From midday we knew it was all up with us. The only question was, whether we would go ashore on a bad spot or not’.

“The Speke then drifted into the bay east of Kitty Miller’s Bay onto the rocks at the eastern beach. (Not so, because a ship of that dimension could not do so). The sea and surf were terrific, and directly the ship struck in but a few fathoms of water the whole ship was swept from stem to stern. The captain gave orders for the lifeboats to be launched and the starboard one was put over the port side with four men in her.”

Unfortunately she capsized and one of the men, Frank Henderson was drowned. One shipmate was quoted as saying: ‘Poor Henderson I can see him now. He struggled in the water like a man who could not swim. Only his face and wildly beating arms were visible, and we were powerless to help him. He was still for about ten seconds, then a huge wave broke over him.’

The rest of the crew survived by hauling themselves precariously in and out of the raging surf down along a line which was thrown ashore and made secure.

Captain Tilston, First Mate Mr Williams, Second Mate Mr Cook, 19 hands, and the two apprentices Rawlins and Poyntz all made it ashore.

The ship’s parrot made it ashore under his own steam but later for some inexplicable reason flew back to the ship where he was later swept overboard and drowned.

The ship’s two cats, forgotten in all the panic and confusion, perished also.

Rescue and recovery

The little wattle and daub pioneer cottage built by the Watt family in 1874 was situated 400 metres directly inland from where the Speke ran aground and broke up.

By 1906 this family had long left the district.

Mr William Harbison JP who owned over 30 farms totalling 5000 acres at the western end of the Island owned this farm too.

As a consequence, the cottage may have been unoccupied at the time of the ship wreck, so any help from this quarter was unlikely.

Mr Charlie Grayden didn’t own or take up occupancy of this property until 1911.The immediate hinterland was still densely covered in ti tree scrub, with some she oaks, eucalypts, wattles and banksias on the rises.

Many farm cottages were dotted around the neighbourhood in 1906, but very few of them were occupied due to adverse commodity prices and sustained drought conditions.

Therefore, there was no one in the immediate vicinity able to assist the beleaguered crew.

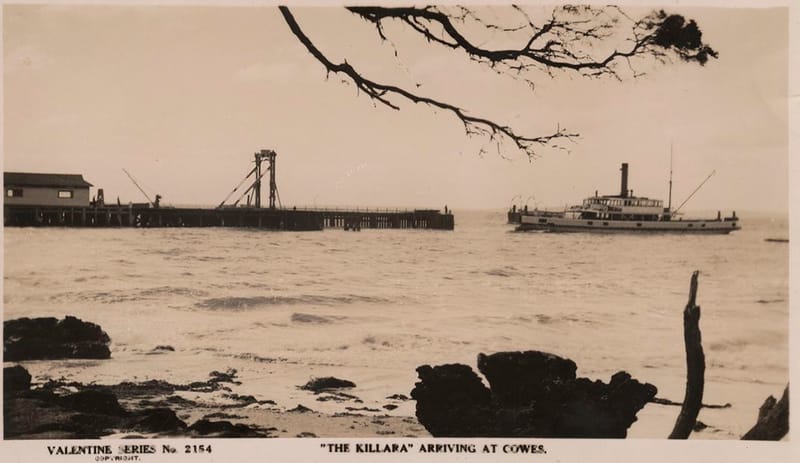

Although the Speke was wrecked at 3 o’clock in the afternoon, the residents of Cowes were unaware of the crew’s plight until 8 o’clock that evening, when they responded immediately.

Half the crew had walked 6½ miles to the Harris farm at Ventnor where they were looked after by Sarah Harris.

The other half of the crew, which included the injured, was found still on the cliff top above the wreck at Watt’s Point, on the east side of Kitty Miller’s Bay.

They were taken to the Isle of Wight Hotel, where they were reunited and offered hot food, a bath and a bed.

Next day they were taken via Hastings to Melbourne where some of the men were hospitalised still suffering from shock, exposure and other injuries.

Due to newspaper publicity at the time, crowds would gather whenever these men were seen together in Melbourne.

They eventually returned to England, by ship, but how many returned to sea duty afterwards is unknown.

As a result of this disaster Captain Tilston was forced to face a three day Marine Board Inquiry in Melbourne where he was found negligent in his duties and had his Master Mariner’s Ticket suspended for twelve months.

In hindsight, that finding was pretty harsh. At the time the weather conditions were appalling. The seas were particularly heavy and rough. The ship was too big and cumbersome to respond to those conditions.

While it was thought at the time that not enough ballast had been loaded in Peru to compensate for the weight of her tall masts, spars and rigging, this was not the reason given by the Marine Board for the ship running aground.

Captain Tilston was accused of bad navigation.

At the time a large fire was burning along the south coast at the western end of Phillip Island.

It may or may not have added to the confusion about whether the light house at Cape Shank or at the Nobbies was clearly visible and which one they could actually see.

Salvaged and sold

The Speke cost 22,000 pounds sterling to build and was sold for salvage to Mr W.J. Kennon, a local farmer, for 12 pounds.

The ship’s brass bell has for many years summoned the parishioners of St John’s Uniting Church (formerly the Presbyterian Church), Cowes.

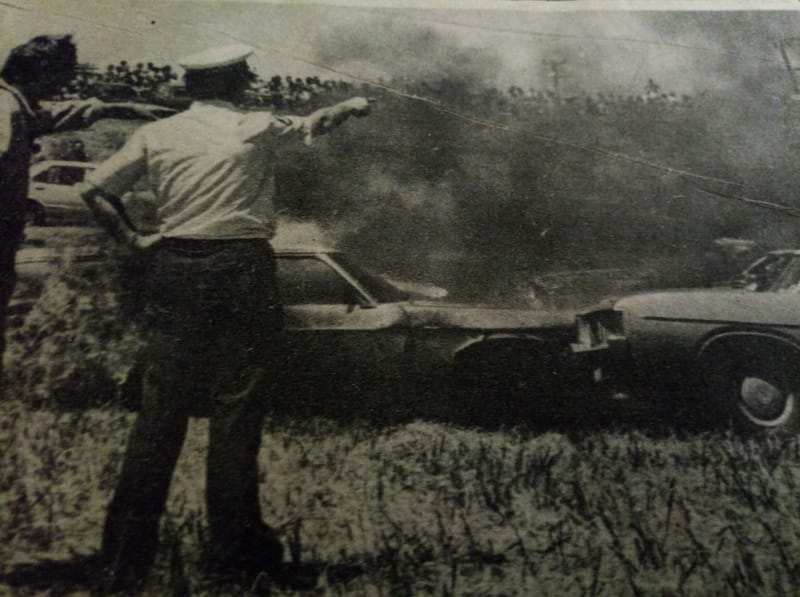

The ornate armchair from the Captain’s saloon aboard the Speke stood for many years in the corner of the bar at the old Isle of Wight Hotel, and went up in smoke when the building was destroyed by fire in 1921.

A big shed at “Hollydene”, now demolished, was built of the Speke’s timbers, and in it for thirty years rested the figurehead, one eye gone, nose broken, and the whole held together with rope salvaged from the wreck.

It had been painted so often that the coating hid the delicate carving of the hair.

Later it was placed in the care of W.E.Thompson, and while in the workshop at “Talofa” it was discovered by schoolboy Stanley Goodall. Taken in hand by Mr Kevin Gerraty, Headmaster, and the senior boys of Cowes State School in 1940, it was tediously pieced together again.

Thirty four years after the Speke’s wrecking, they found the original mounting timbers still fastened to the only remaining fragment of the wreck on the beach.

The repaired figurehead was unveiled by G.S. Browne, Professor of Education, Melbourne University, on the 20th November 1941.

What happened to the torso section of the figurehead originally a figure nine feet four inches long, exquisitely carved in wood, of a lady, with a flowing white dress, with blue cuffs and collar, carrying a large bunch of daffodils and beautifully painted by the famous shipyard woodcarver Dick Cowell prior to the Speke’s launch, is not clear.

Only the larger than life size head of the Speke’s magnificent figurehead remains and is displayed in the Phillip Island Historical Society’s Rooms at Cowes.

One of the Speke’s two huge anchors lay for seventy years in Kitty Miller’s Bay where it was exposed at each low tide.

It was dragged there during Mr Kennon’s salvage work but weighing three tons, proved too heavy to recover until Keith Grayden’s old army blitz wagon was used in the 1970’s to haul it off the beach.

It lay in the works depot formerly operated by the Shire of Phillip Island.

The evidence given at the Marine Board Inquiry suggests instead it is lying on the sea floor somewhere off shore between Cape Woolamai and Kitty Miller’s Bay.

In 1906 the massive broken masts and spars were sawn up and used as gate posts and building material around several farms on Phillip Island. Some are still in situ.

The teak decking was used among other things as weatherboards to clad and floor the dining room and recreation/dance hall at Broadwater Guest House, Lovers Walk, Cowes.

When this fine old guest house ceased to operate as such the whole building was transported out to Mr Peter Forrest’s farm on Harbison Road, opposite the Oswin Roberts Reserve, where it is still in situ (now painted dark green) and was used as a shearing shed for many years.

The Speke’s ropes and hawsers were still being used by Mr Ken McKinlay, a local Ventnor professional fisherman before he retired in the early 1970’s.

One of the many heavy companion ways was converted into a big horse drawn farm sled before the First World War by Mr Bert Grayden, which was later converted into a smudger by his son Neil.

The remnants of this implement still remain under the sheoaks near Neil Grayden’s shearing shed next door to the race track.

The round Peruvian bluey green river stones which made up the Speke’s ballast are strewn along the beach where the wreck now lies. To the unknowing and mystified geologist these rocks are not found anywhere else in Australia and therefore cause some initial excitement until their secret is revealed.

Nowadays, only the rusty bowsprit and anchor chamber section of the Speke remains, lying exposed on its side about 100 metres further on shore from where the ship ran aground, surrounded by several twisted rusting pitted sheets of steel plate and some of the river worn ballast stones from Peru.

Nearly three quarters of the Speke’s hull lies hidden in an east/west direction on the sandy sea bottom in five fathoms or roughly ten metres of water.

Over the last fifty years, the occasional experienced scuba diver has reported very dangerous diving conditions due to the strong currents and presence of swirling kelp.

Visibility is not good because of the ever present bands or layers of stirred up sand.

Very little of the wreck remains on the seafloor.

Sometimes it is buried in the constantly moving layers of sand.

Occasionally, the submerged portion of the wreck lies exposed like a flat filleted fish, always reminding the diver of the sea’s awesome destructive force.