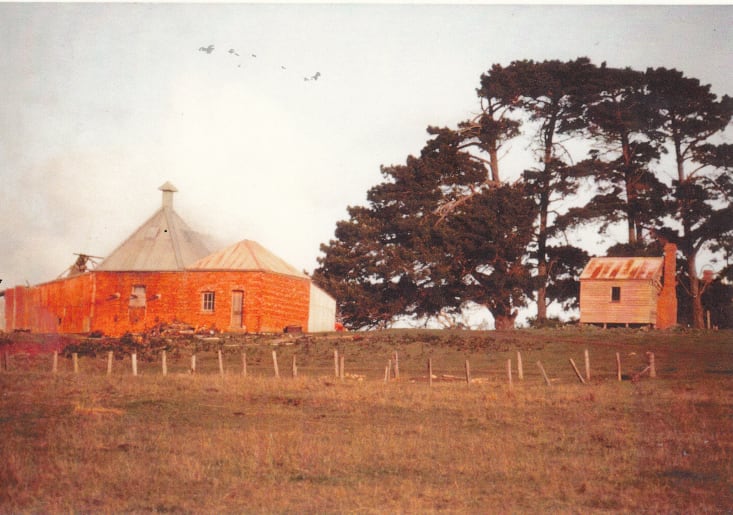

Joseph Richardson’s kiln in Ventnor Beach Road, built on Richardsons Hill (known locally as Hurricane Hill) Built in the early 1870’s, it was the largest kiln on the island. It had a horse works that went around and around to run a shaft which turned the cutter.

This article in The Weekly Times, dated November 11, 1985, reads: “The last man to grow chicory in Australia, Phillip Island’s Jim McFee.The last fully operational kiln in Australia may have been used for the last time if another chicory buyer cannot be found”.

Chicory was used in coffee essences or as a coffee substitute for centuries

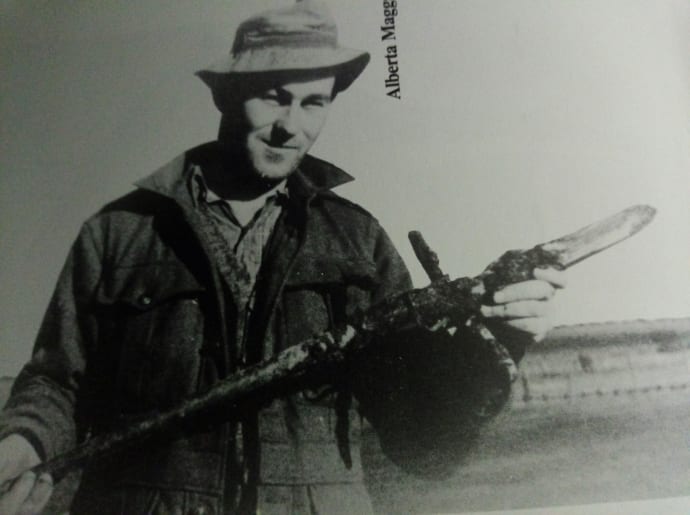

Stan Grayden, a great-grandson of island pioneers Sarah and Joseph Richardson, with his chicory devil, a tool developed by a Maffra engineering firm which adapted a sugar beet lifter for chicory use.

A kiln just off Ventnor Road

This kiln is on the Rhyll Road, near the Phillip Island Road

Following its renovation, which finished in 2015, this kiln has become one of the island’s architectural gems

Monuments to the island’s early years

Chicory kilns have become such an accepted part of Phillip Island’s landscape, they can be easily overlooked.

But in many ways, the dilapidated, slim brick towers stand as monuments to the island’s early development.

According to the Heritage Council of Victoria, of the 33 kilns known to remain in Victoria, 28 are located on Phillip and French islands, one at Corinella and one in Bacchus Marsh.

Chicory was grown on the island from 1870 and an article in The Weekly Times in November 1985, states the last people to grow chicory in Australia was the island’s Jim McFee and Wayne Drennan.

The article says after the men harvested their 18 tonne crop in May “the only Australian buyer had indicated it does not require a crop next year”, which marked the end of the industry two years later.

These days the chicory family is known for its trendy bitter salad leaves, such as radicchio or endive, but the chicory grown by Phillip Island farmers resembled a parsnip with broad flat leaves.

From the time of the Napoleonic Wars it was customary to blend chicory with coffee and given that coffee was more expensive, chicory was for centuries used as a beverage. The dried roots would be ground into a fine powder, which made a tangy, bitter-tasting caramelised essence.

The chicory industry reached its peak during the 1940s when more than 75 per cent of Australia’s requirement was grown in the Western Port area. On Phillip Island, French Island and in Corinella and Grantville districts, there were 164 growers.

Early history

Chicory was first grown on Phillip Island in 1870, and the first two or three years was shipped green and taken to Melbourne by Captain John Lock in his ketch.

According to the Phillip Island and District Historical Society , in 1873, the first chicory kiln was built by John and Solomon West, in Thompson Avenue, Cowes, near the Esplanade.

A second kiln was built around 1879 by early settler Joseph Richardson, the largest to be built, powered by horses.

In the early 1880s, there were about 230 acres of chicory grown, yielding 960 tons.

At this early time, chicory was harvested or dug out of the ground with picks and about 1884, a tool was made with a 4cm-wide blade, shaped like a spade, called a “chicory devil”. This implement was used until 1930, when a single furrow plough drawn by two horses was used to lift the root of the chicory, doing away with the back-breaking work of digging every root.

With mechanization the crop was then lifted with a ripper attached to a tractor which made the harvesting of crops much easier.

Growing, processing

A good annual rainfall, almost free from frosts and volcanic soil, made this area most suitable for chicory production. Some believed that proximity to the sea was an advantage in some way.

“Attempts to grow the crop further inland generally resulted in corky or pithy roots, unsatisfactory for extraction of essence,” said The Weekly Times article.

Weather permitting the chicory seed was sown from mid-September to the end of October.

The worst pests which had to be dealt with was the lucern flea and the red legged earth mite, which attacked the young plants as they appeared through the soil.

Harvesting started in mid-April or early-May, with the root topped, bagged and taken to the kiln to be washed.

It was put through a cutting machine, with the cut slices carried on an elevator to the drying floor, which was a heavy wire gauze set about 3-4 metres above a wood burning furnace.

The heat, which for the first three or four hours was intense, was gradually reduced as the moisture dried out.

The average time required to dry was about 24 hours and up to 3 tons of wood was needed to dry 1 ton of the kiln dried root.

After the chicory was dried it was bagged and sent to Melbourne to the Chicory Marketing Board for sale, where it was bought by tea and coffee merchants, who roasted the chicory again, and put it through a kibbling machine which broke it into small pieces.

It was then ready to be blended with coffee beans and made into coffee essence, or ground into powder to be blended with coffee.

Chicory contains medicinal properties, relatively high in sugar and counteracts the drug caffeine in the coffee bean.

Marketing, final years

In 1934, when the price of chicory had fallen far below a payable price, it was decided by a majority of growers to form a voluntary pool and sell from the pool at ?45 per ton.

The merchants refused to pay this price and consequently not an ounce of chicory was sold for two years; by this time most of the growers were virtually insolvent.

In desperation three representatives were sent to Melbourne to talk to a Member of Parliament who was sympathetic, mentioning the growers’ difficulties to the then Minister of Agriculture in the Dunstan Government.

In April 1936, the Chicory Marketing Board was constituted with two representatives from the growers and one government nominee appointed. At the first meeting of the board, Phillip Island’s Rupert Harris was elected chairman and held the office for more than 34 years.

All chicory grown in Victoria had to be vested in the board – it negotiated sales with coffee merchants, stored temporary excess for release through the year and arranged payment to the producers at a pre-set price of $225 per ton of dried chicory.

The scheme proved so successful that the South Australian growers also used the services of the Victorian Marketing Board.

In 1956 a request was made by the Phillip Island Shire that a road transport be allowed for island chicory growers, owing to changed market conditions – because of the absorption of moisture from the air, and the root having to be so crisply dried, breakage in transit had to be avoided as the size needed to be maintained for processing with coffee.

The last crop to be grown was at Rhyll by Jim McFee in 1987, whose kiln had been operating since 1954.

Inspiring an island-only architecture

Chicory kilns may stand as sentinels to Phillip Island’s past, but residents with an eye for design see them as architectural opportunities.

Drive around the island and kilns of old have clearly inspired a modern, island-only style of construction, with signature turrets and chimneys on roof tops, alongside buildings with slim widths and long vertical rises.

Charles Anderson is one such resident, whose home gives a nod to this past agricultural industry.

Located in Ventnor, Charles bought the property in 2006, then employing architects to convert his heritage-listed kiln (circa 1890s) into the family residence, with renovations finishing in 2015.

“It was not in great shape but we never wanted to bulldoze it but create something that was meaningful and kept the character intact,” Charles says.

“We were interested in living in a building that has some history rather than a new building and the form of a chicory kiln is very interesting, it’s part of the history of the island.

“From our research we understand this kiln was one of the last to be functioning on the island, up to the 1970s. We’ve even met people who worked on it.”

To do justice to the project, Charles initially travelled around the island documenting kilns before they began the massive work of stripping the interior and stabilising the concrete structure – one of the few kilns on the island constructed from this material.

“The original design was to keep all the walls intact and not change anything but when we got up close we discovered two of the upper side walls were too far gone so we had to replace those.”

Aside from this change, the building’s envelope remains the same, with old venting points transformed into windows, and in the chimney a skylight has been installed that opens and shut for ventilation.

“We sleep under the skylight and see the night sky.

“But the beauty of the kilns from an architectural point of view is their sustainable design. Because they had a fire in the bottom the walls are over 1 metre thick, which makes a great thermal mass.

“In summer it maintains a certain degree of coolness in the building and in winter whenever the sun shines on it, the building retains heat.”

Such is the renown of the building, it has been given the name A House for Hermes 05, which identifies the project as part of a series of art and design works under this name.